Jewish philosophy

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Jews and Judaism |

|---|

|

| Who is a Jew? · Etymology · Culture |

|

God in Judaism (Names)

Principles of faith · Mitzvot (613) Halakha · Shabbat · Holidays Prayer · Tzedakah Brit · Bar / Bat Mitzvah Marriage · Bereavement Philosophy · Ethics · Kabbalah Customs · Synagogue · Rabbi |

|

Ashkenazi · Sephardi · Mizrahi

Romaniote · Italki · Yemenite African · Beta Israel · Bukharan · Georgian • German · Mountain · Chinese Indian · Khazars · Karaim • Krymchaks • Samaritans • Crypto-Jews |

|

Population

|

|

Denominations

Alternative · Conservative

Humanistic · Karaite · Liberal · Orthodox · Reconstructionist Reform · Renewal · Traditional |

|

Timeline · Leaders

Ancient · Kingdom of Judah Temple Babylonian exile Yehud Medinata Hasmoneans · Sanhedrin Schisms · Pharisees Jewish-Roman wars Christianity and Judaism Islam and Judaism Diaspora · Middle Ages Sabbateans · Hasidism · Haskalah Emancipation · Holocaust · Aliyah Israel (history) Arab conflict · Land of Israel Baal teshuva · Persecution Antisemitism (history) |

|

Politics

|

| Part of a series on Philosophy Jewish philosophy |

|

|

|

| This template covers Jewish philosophers who articulated traditional or revisionist Jewish theology in terms of the Western philosophical tradition. Their relation to wider theologians and mystics of Judaism are covered in Jewish philosophy main article | |

|---|---|

| Hellenistic Jewish philosophy

|

|

|

People: Position in Western Philosophy: |

|

| Medieval Jewish philosophy

|

|

|

People: Position in Rabbinic Judaism: Position in Western Philosophy: Topics: |

|

| Modern Jewish philosophy

|

|

|

People: Position in Modern Judaism: |

|

Jewish philosophy includes all philosophical activity carried out by Jews, or, in relation to the religion of Judaism. Jewish philosophy, until modern Enlightenment and Emancipation, was pre-occupied with attempts to reconcile coherent new ideas into the tradition of Rabbinic Judaism; thus organizing emergent ideas that are not necessarily Jewish into a uniquely Jewish scholastic framework and world-view. With their acceptance into modern society, Jews with secular educations embraced or developed entirely new philosophies to meet the demands of a world in which they now found themselves.

Medieval re-discovery of Greek thought among Gaonim of 10th century Babylonian academies brought rationalist philosophy into Biblical-Talmudic Judaism, which later competed for the mainstream with emergent mysticism. Both schools would become part of classic Rabbinic literature, though the decline of scholastic rationalism coincided with historical events which drew Jews to mystical theology. For European Jews, emancipation and encounter with secular thought from the 18th-century onwards altered how philosophy was viewed. Oriental and Eastern European communities had later and more ambivalent interaction with secular culture than in Western Europe. In the varied responses to modernity, Jewish philosophical ideas were developed across the range of emerging religious denominations. These developments could be seen as either continuations, or breaks, with the canon of Rabbinic philosophy of the Middle Ages, as well as the other historical dialectic aspects of Jewish thought, and resulted in diverse contemporary Jewish attitudes to philosophical methods.

Ancient Jewish philosophy

Biblical philosophy

Talmudists suggest that Abraham introduced a philosophy learned from Melchizedek[1]; Some Jews ascribe the Sefer Yetzirah "Book of Creation" to Abraham [2]. Talmud [3] describes how Abraham understood this world to have a creator and director by comparing this world to "a house with a light in it", what is now called the Argument from design. Many scholars assume that Melchizedek influenced Abram's views, but to what extent Melchizedek influenced Abraham, and the true provenance of Sefer Yetzirah, continues to be debated. The Book of Psalms contains invitations to "admire the wisdom of Hashem through his works"; from this, some scholars suggest, Judaism harbors a Philosophical under-current. The Book of Ecclesiastes is often considered to be the only genuine Philosophical work in the Hebrew Bible, it's author seeks to understand the place of human beings in the world, and life's meaning.

Philo of Alexandria

Philo attempted to fuse and harmonize Greek Philosophy and Judaism via allegory which he learned from Jewish exegesis and the Stoics [4]. Philo attempted to make his philosophy the means of defending and justifying Jewish religious truths. These truths he regarded as fixed and determinate, and philosophy was used as an aid to truth, and a means of arriving at it. To this end Philo chose from philosophical tenets of Greeks, refusing those that did not harmonize with Judaism such as Aristotle's doctrine of the eternity and indestructibility of the world.

Dr. Bernard Revel, in dissertation on "Karaite Halacha", points to writings of a 10th century Karaite, Ya'qub al-Qirqisani, who quotes Philo, illustrating how Karaites made use of Philo's works in development of Karaism. Philo's works became important to Medieval Christian scholars who leveraged the work of Karaites to lend credence to their claims that "these are the beliefs of Jews" - a technically correct, yet mendacious, attribution.

Jewish scholarship after destruction of Second Temple

With destruction of the Second Temple Judaism was in disarray [5] - Exilarchs fled to safety in Nehardea, civil war severed the fabric of Jewish culture, Roman genocide, enslavement and expulsion from Jerusalem were harsh blows to Jewish society and its leaders. Rabbi Yochanan Ben Zakkai, in shrewd maneuvers, saved the Sanhedrin and moved it to Yavne. Shortly thereafter, Council of Yavne met to preserve Rabbinic Judaism, formulate texts and revise views.

Rabbi Akiva

Rabbi Akiva ben Joseph was the only tanna to suggest a religious philosophy [6] . Rabbi Akiva's works illustrate 1.) "How favored is man, for he was created after an image "for in an image, Elohim made man" (Gen. ix. 6)", 2.) "Everything is foreseen; but freedom [of will] is given to every man", 3.) "The world is governed by mercy... but the divine decision is made by the preponderance of the good or bad in one's actions".

Hakira – investigation

After Bar Kochba Revolt, Rabbinic scholars gathered in Tiberias and Safed to re-assemble and re-assess Judaism, its laws, theology, liturgy, beliefs and leadership structure. In 219 CE, the Sura Academy is founded, by Abba Arika, from which Jewish Kalam emerges many centuries later. For the next five centuries Talmudic Academies focus upon reconstituting Judaism; little, if any, philosophic investigation in Jewish Academies is pursued.

Who influences whom?

Rabbinic Judaism had no philosophy until challenged by Islam, Karaism, and Christianity - with Mishnah, Talmud and Tanach, there was no need for a philosophic framework. From an economic viewpoint, Radhanite Trade dominance was being usurped by coordinated Christian and Islamic forced-conversions, and torture, compelling Jewish scholars to understand nascent economic threats. These investigations triggered new ideas and intellectual exchange among Jewish and Islamic scholars in the areas of jurisprudence, mathematics, astronomy, logic and philosophy. Jewish scholars influenced Islamic scholars and Islamic scholars influenced Jewish scholars. Contemporary scholars continue to debate who was Muslim and who was Jew - some "Islamic scholars" were "Jewish scholars" prior to forced conversion to Islam, some Jewish scholars willingly converted to Islam, such as Abdullah ibn Salam, while others later reverted to Judaism, and still others, born and raised as Jews, were ambiguous in their religious beliefs such as Ibn al-Rawandi- though lived according to the customs of their neighbors.

Around 700 CE, `Amr ibn `Ubayd Abu `Uthman al-Basri introduces two streams of thought that influence Jewish, Islamic and Christian scholars

- 1.) The Qadariyya and,

- 2.) The Mu'tazilah.

The story of Mu'tazilah and Qadariyya is as important, if not more so, as the intellectual symbiosis of Judaism and Islam in Islamic Spain.

Around 733 CE, Mar Natronai ben Habibai moves to Kairouan, then to Spain, transcribing Talmud Bavli for the Academy at Kairouan from memory - later taking a copy with him to Spain.[7].

Karaism

Karaites were the first Jewish Sect to subject Judaism to Mu'tazilah. Rejecting Talmud and Rabbinic tradition, Karaites took liberty to reinterpret Tanach as they saw fit. This meant abandoning foundational Jewish belief structures. Some scholars suggest that the major impetus for the formation of Karaism was a reaction to the rapid rise of Shi'a Islam, which recognized Judaism as a fellow monotheistic faith, but claimed that it detracted from monotheism by deferring to Rabbinic authority. Karaites absorbed certain aspects of Jewish sects such as Isawites (Shi'ism), Malikites (Sunnis) and Yudghanites (Sufis), who were influenced by East-Islamic scholarship yet deferred to Ash'ari when contemplating the sciences.

Philosophic synthesis begins

The spread of Islam throughout the Middle East and North Africa rendered Muslim all that was once Jewish. Greek philosophy, science, medicine and mathematics was absorbed by Jewish scholars living in the Arab world due to Arabic translations of those texts; remnants of the Library of Alexandria. Early Jewish converts to Islam brought with them stories from their heritage, known as Isra'il'iyat, which told of the Banu Isra'il, the pious men of ancient Israel. One of the most famous early Islamic mystics - Sufi Hasan al-Basri introduced numerous Isra'il'iyat legends into Islamic scholarship, stories that went on to become representative of Islamic mystical ideas of piety of Sufism.

Hai Gaon, at Pumbeditha Academy, begins a new phase in Jewish scholarship and investigation (Hakira); Hai Gaon augments Talmudic scholarship with non-Jewish studies. Hai Gaon was a savant with an exact knowledge of the theological movements of his time so much so that Moses ibn Ezra called him a mutakallim. Hai was competent to argue with followers of Qadariyya and Mutazilites, sometimes adopting their polemic methods. Through correspondence with Talmudic Academies at Kairouan, Cordoba and Lucena, Hai Gaon passes along his discoveries to Talmudic scholars therein.

Jewish philosophy before Maimonides

Medieval Jewish philosophy

Saadia Gaon

Saadia Gaon, son of a proselyte, is considered the greatest early Jewish philosopher. During Saadia's early years in Tulunid Egypt, the Fatimid Caliphate ruled Egypt; leaders of the Tulunids were Ismaili Imams. Their influence upon the Jewish academies of Egypt resonate in the works of Saadia. Saadia's Emunoth ve-Deoth ("Beliefs and opinions") was originally called Kitab al-Amanat wal-l'tikadat ("Book of the Articles of Faith and Doctrines of Dogma"); it was the first systematic presentation and philosophic foundation of the dogmas of Judaism, completed at Sura Academy in 933 CE.

In "Book of the Articles of Faith and Doctrines of Dogma" Saadia declares the rationality of the Jewish religion, with the caveat that reason must capitulate wherever it contradicts tradition. Dogma takes precedence over reason. Saadia closely followed the rules of the Mu'tazilah school of Abu Ali al-Jubba'i in composing his works[8][9]. It was Saadia, who laid foundations for Jewish rationalist theology which built upon the work of Mu'tazilah, thereby shifting Rabbinic Judaism from mythical explanations of the Rabbis to reasoned explanations of the intellect. Saadia advances the criticisms of Mu'tazilah, by Ibn al-Rawandi[10].

David Ibn Marwān al-Mukammas al-Rakki

David ben Merwan al-Mukkamas was author of the earliest known Jewish philosophical work of the Middle Ages, a commentary on Sefer Yetzirah (Book of Creation); he is regarded as the father of Jewish medieval philosophy. Al-Mukammas was first to introduce the methods of Kalam into Judaism and the first Jew to mention Aristotle in his writings. He was a proselyte of Rabbinic Judaism (not Karaism as some argue); al-Mikammas was a student of physician, and renowned Christian philosopher, Hana. His close interaction with Hana, and his familial affiliation with Islam gave al-Mukammas a unique view of religious belief and theology. In 1898 Abraham Harkavy discovered, in Imperial Library of St. Petersburg, fifteen of the twenty chapters of David's philosophical work entitled Ishrun Maḳalat (Twenty Chapters) of which 15 survive.

Samuel Ha-Nagid

Shmuel Ha-Nagid, born in Mérida - lived in Cordoba, was a child prodigy and student of Rabbi Hanoch ben Moshe. Shmuel Ha-Nagid, Hasdai Ibn Shaprut, and Rabbi Moshe ben Hanoch founded the Lucena Yeshiva that produced such brilliant scholars as Rabbi Yitzhak ibn Ghiath and Rabbi Maimon ben Yosef (father of Maimonides). Ha-Nagid's son, Yosef, provided refuge for two sons of (Hezekiah Gaon); Daud Ibn Chizkiya Gaon Ha-Nasi and Yitzhak Ibn Chizkiya Gaon Ha-Nasi - Patriarchs of the "Ibn Yahya" and "Shealtiel/Kalonymos/Todros" families respectively. Ha-Nagid as a monumental man whose patrician care of the Jewish Community will forever be rememberedl. Though not a philosopher, he did build the infrastructure to allow philosophers to thrive.

Yitzhak ben Yaakob HaKohen al-Fasi

Rabbi Yitzhak ben Yakob HaKohen al-Fasi was a student of Nissim Gaon. al-Fasi is best known for his work of halachah, the legal code Sefer Ha-halachot, considered the first fundamental work in halachic literature. al-Fasi wrote Talmud Katan ("the Little Talmud"). At the close of the Middle Ages, when the Talmud was banned in Italy, al-Fasi's Talmud Katan was exempted so that from the 16th to the 19th centuries his work was the primary subject of study of the Italian Jewish community. al-Fasi occupies an important place in the development of the Sephardi method of studying the Talmud and influencing the growth of rational philosophic exploration of Jewish Canon. In contrast to Tosafists who made the Talmud more intricate, al-Fasi taught his students to simplify the Talmud and free it from casuistic detail.

Solomon ibn Gabirol

Shlomo ben Yehuda ibn Gevirol, born in Málaga then moved to Valencia. Ibn Gabirol was one of the first teachers of Neoplatonism in Europe. His role has been compared to that of Philo. Ibn Gabirol occidentalized Greco-Arabic philosophy and restored it to Europe. The philosophical teachings of Philo and Ibn Gabirol were largely ignored by fellow Jews; the parallel may be extended by adding that Philo and Ibn Gabirol, alike, exercised considerable influence in secular circles; Philo upon early Christianity, and Ibn Gabirol upon the scholars of medieval Christianity. Christian scholars, including Albertus Magnus and Thomas Aquinas, defer to him frequently.

Abraham bar-Hiyya Ha-Nasi

Abraham bar Hiyya Ha-Nasi, of Barcelona and later Arles-Provence, was a student of his father Hiyya al-Daudi Ha-Nasi. Abraham bar Ḥiyya was one of the most important figures in the scientific movement which made the Jews of Provence, Spain, and Italy the intermediaries between Averroism, Mu'tazilah and the Christian world. He aided this scientific movement by original works, translations and as interpreter for another translator, Plato of Tivoli. bar-Hiyya's best student was Abraham Ibn Ezra. bar-Hiyya's philosophical works, are ("Meditation of the Soul"), an ethical work written from a rationalistic religious viewpoint, and an apologetic epistle addressed to Judah ben Barzilai al-Barzeloni.

Nethan'el al-Fayyumi

Natan'el al-Fayyumi[11], of Yemen, was the twelfth-century author of Bustan al-Uqul ("Garden of Intellects"), a Jewish version of Ismaili Shi'ite doctrines. Like the Ismailis, Nethanel al-Fayyumi argued that Hashem sent different prophets to various nations of the world, containing legislations suited to the particular temperament of each individual nation. Ismaili doctrine holds that a single universal religious truth lies at the root of the different religions. Some Jews accepted this model of religious pluralism, leading them to view Prophet Mohammed as a legitimate prophet, though not Jewish, sent to preach to the Arabs, just as the Hebrew prophets had been sent to deliver their messages to Israel; others refused this notion in entirety. Nethanel's son Yakob ben Nethanel Ibn al-Fayyumi turned to Maimonides, asking urgently for counsel on how to deal with forced conversions to Islam and religious persecutions at the hand of Saladin. Maimonides' response was Iggret Teiman

Bahya ben Joseph ibn Paquda

Bahye ben Yosef Ibn Paquda, of Zaragoza, was author of the first Jewish system of ethics Al Hidayah ila Faraid al-hulub, ("Guide to the Duties of the Heart"). Bahya often followed the method of the Arabian encyclopedists known as "the Brethren of Purity" but adopts some of Sufi tenets rather than Ismaili. According to Bahya, the Torah appeals to reason and knowledge as proofs of Hashem's existence. It is therefore a duty incumbent upon every one to make Hashem an object of speculative reason and knowledge, in order to arrive at true faith. Baḥya borrows from Sufism and Jewish Kalam integrating them into Neoplatonism. Proof that Bahya borrowed from Sufism is underscored by the fact that the title of his eighth gate, Muḥasabat al-Nafs ("Self-Examination"), is reminiscent of the Sufi Abu Abd Allah Ḥarith Ibn-Asad, who has been surnamed El Muḥasib ("the self-examiner"), because—say his biographers—"he was always immersed in introspection"[12]

Yehuda Ha-Levi and the Kuzari

Rabbi Judah Ha-Levi, of Toledo, defended Rabbinic Judaism against Islam, Christianity and Karaism. He was a student of Moses Ibn Ezra whose education came from Isaac ibn Ghiyyat; trained as a Rationalist, he shed it in favor of Neoplatonism. Like Al-Ghazali, Judah Ha-Levi attempted to liberate religion from the bondage of philosophical systems. In particular, in a work written in Arabic Kitab al-Ḥujjah wal-Dalil fi Nuṣr al-Din al-Dhalil, translated by Judah ben Saul ibn Tibbon, by the title Sefer ha-Kuzari he elaborates upon his views of Judaism relative to other religions of the time.

Abraham ibn Daud

Abraham Ibn Daud was a student of Rabbi Baruch ben Yitzhak Ibn Albalia, his maternal uncle. Ibn Daud's philosophical work written in Arabic, Al-'akidah al-Rafiyah ("The Sublime Faith"), has been preserved in Hebrew by the title Emunah Ramah. Ibn Daud did not introduce a new philosophy, but he was the first to introduce a more thorough systematic form derived from Aristotle. Accordingly, Hasdai Crescas mentions Ibn Daud as the only Jewish philosopher among the predecessors of Maimonides[13]. Overshadowed by Maimonides, ibn Daud's Emunah Ramah, a work to which Maimonides was indebted, received little notice from later philosophers. "True philosophy", according to Ibn Daud, "does not entice us from religion; it tends rather to strengthen and solidify it. Moreover, it is the duty of every thinking Jew to become acquainted with the harmony existing between the fundamental doctrines of Judaism and those of philosophy, and, wherever they seem to contradict one another, to seek a mode of reconciling them".

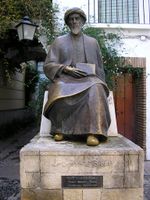

==== The Rambam - Maimonides ====

Maimonides wrote The Guide for the Perplexed - his most influential philosophic work. He was a student of his father, Rabbi Maimon ben Yosef (a student of Joseph ibn Migash) in Cordoba, Spain. When his family fled Spain, for Fez, Maimonides enrolled in the Academy of Fez and studied under Rabbi Yehuda Ha-Kohen Ibn Soussan - a student of Isaac Alfasi. Maimonides strove to reconcile Aristotelian philosophy and science with the teachings of Torah. In some ways his position was parallel to that of Averroes; in reaction to the attacks on Avicennian Aristotelism, Maimonides embraced and defended a stricter Aristotelism without Neoplatonic additions. The principles which inspired all of Maimonides' philosophical activity was identical those of Abraham Ibn Daud: there can be no contradiction between the truths which Hashem has revealed and the findings of the human intellect in science and philosophy. Mainmonides departed from the teachings of Aristotle by suggesting that the world is not eternal, as Aristotle taught, but was created ex nihilo. In "Guide for the Perplexed" (1:17 & 2:11)" Maimonides explains that Israel lost its Mesorah in exile, and with it "we lost our science and philosophy - only to be rejuvenated in Al Andalus within the context of interaction and intellectual investigation of Jewish, Christian and Muslim texts.

Notable Jewish philosophers pre-Maimonides

- Abraham ibn Ezra

- Isaac ibn Ghiyyat

- Moses ibn Ezra

- Yehuda Alharizi

- Hillel of Verona

- Joseph ibn Tzaddik

- Samuel ibn Tibbon

- Jacob Anatoli son-in-law of Samuel ibn Tibbon

Jewish Philosophy after Maimonides

Maimonides writings almost immediately came under attack from Karaites, Dominican Christians, Tosafists of Provence, Ashkenaz and Al Andalus. His genius was obvious, protests centered around his writings. Scholars suggest that Maimonides instigated the Maimonidean Controversy when he verbally attacked Samuel ben Ali Ha-Levi al-Dastur ("Gaon of Baghdad") as "one whom people accustom from his youth to believe that there is none like him in his generation," and he sharply attack the "monetary demands" of the academies. al-Dasturwas an anti-Maimonidean operating in Babylon to undermine the works of Maimonides and those of Maimonides' patrons (the Al-Constantini Family from North Africa). To illustrate the reach of the Maimonidean Controversy, al-Dastur, the chief opponent of Maimonides in the East, was excommunicated by Daud Ibn Hodaya al Daudi (Exilarch of Mosul).

In Western Europe, the controversy was halted by the burning of Maimonides' works by Christian Dominicans, in 1232. Avraham son of Rambam, continued fighting for his father's beliefs in the East; desecration of Maimonides' tomb, at Tiberias by Jews, was a profound shock to Jews throughout the Diaspora and caused all to pause and reflect upon what was being done to the fabric of Jewish Culture.

Maimonidean controversy flared up again[14] at the beginning of the fourteenth century when Rabbi Shlomo ben Aderet, under influence from Asher ben Jehiel, issued a herem on "any member of the community who, being under twenty-five years, shall study the works of the Greeks on natural science and metaphysics."

Contemporary Kabbalists, Tosafists and Rationalists continue to engage in lively, sometimes caustic, debate in support of their positions and influence in the Jewish world. At the center of many of these debates are 1) "Guide for the Perplexed", 2) "13 Principles of Faith", 3) "Mishnah Torah", and 4) his commentary on Anusim.

Medieval and pre-Renaissance Jewish philosophy

Yosef ben Yehuda of Ceuta

Joseph ben Judah of Ceuta, of Ceuta, was the son of Rabbi Yehuda Ha-Kohen Ibn Soussan and a student of Maimonides for whom the "Guide for the Perplexed" is written. Yosef traveled from Alexandria to Fustat to study logic, mathematics, and astronomy under Maimonides. Philosophically, Yosef's dissertation, in Arabic, on the problem of "Creation" is suspected to have been written before contact with Maimonides. It is entitled Ma'amar bimehuyav ha-metsiut ve'eykhut sidur ha-devarim mimenu vehidush ha'olam ("A Treatise as to (1) Necessary Existence (2) The Procedure of Things from the Necessary Existence and (3) The Creation of the World").

Shemtob Ben Joseph Ibn Falaquera

Shem-Tov ibn Falaquera was a Spanish-born philosopher who pursued reconciliation between Jewish dogma and philosophy. Scholars speculate he was a student of Rabbi David Kimhi whose family fled Spain to Narbonne[15]. Ibn Falaquera lived an ascetic live of solitude[16]. Ibn Falaquera's two leading philosophic authorities were Averroes and Maimonides. Ibn Falaquera defended the "Guide for the Perplexed" against attacks of anti-Maimonideans[17]. He knew the works of the Islamic philosophers better than any Jewish scholar of his time, and made many of them available to other jewish scholars – often without attribution (Reshit Hokhmah). Ibn Falaquera did not hesitate to modify Islamic philosophic texts their texts when it suited his purposes. For example, Ibn Falaquera turned Alfarabi's account of the origin of philosophic religion into a discussion of the origin of the "virtuous city". Ibn Falaquera's other woirks include, but are not limited to Iggeret Hanhagat ha-Guf we ha-Nefesh, a treatise in verse on the control of the body and the soul.

- Iggeret ha-Wikkuaḥ, a dialogue between a religious Jew and a Jewish philosopher on the harmony of philosophy and religion.

- Reshit Ḥokmah, treating of moral duties, of the sciences, and of the necessity of studying philosophy.

- Sefer ha-Ma'alot, on different degrees of human perfection.

- Moreh ha-Moreh, commentary on the philosophical part of Maimonides' "Guide for the Perplexed".

Gersonides

Rabbi Levi ben Gershon was a student of his father Gerson ben Solomon of Arles, who in turn was a student of Shem-Tov ibn Falaquera. Gersonides is best known for his work Milhamot HaShem ("Wars of the Lord"). Milhamot HaShem is modelled after the "Guide for the Perplexed". Milhamot HaShem is an Averroistic criticism of reconciliation of Aristotelism and Jewish dogma as presented in that work. Gersonides and his father were avid students of the works of Alexander of Aphrodisias, Aristotle, Empedocles, Galen, Hippocrates, Homer, Plato, Ptolemy, Pythagoras, Themistius, Theophrastus, Ali ibn Abbas al-Magusi, Ali ibn Ridwan, Averroes, Avicenna, Qusta ibn Luqa, Al-Farabi, Al-Fergani, Chonain, Isaac Israeli, Ibn Tufail, Ibn Zuhr, Isaac Alfasi, and Maimonides. Gersonides held that Hashem does not have complete foreknowledge of human acts. "Gersonides, bothered by the old question of how Hashem's foreknowledge is compatible with human freedom, suggests that what Hashem knows beforehand is all the choices open to each individual. Hashem does not know, however, which choice the individual, in his freedom, will make."[18].

Moses Narboni

Moses ben Joshua composed commentaries on Islamic philosophical works. As an admirer of Averroes; he devoted a great deal of study to his works and wrote commentaries on a number of them. His best know work is his Shelemut ha-Nefesh ("Treatise on the Perfection of the Soul"). Moses began studying philosophy with his father when he was thirteen later studying with Moses ben David Caslari and Abraham ben David Caslari - both of whom were students of Kalonymus ben Kalonymus. Moses believed that Judaism was a guide to the highest degree of theoretical and moral truth. He believed that the Torah had both a simple, direct meaning accessible to the average reader as well as a deeper, metaphysical meaning accessible to thinkers. Moses rejected the belief in miracles, instead believing they could be explained, and defended man's free will by philosophical arguments.

Isaac ben Sheshet Perfet

Isaac ben Sheshet Perfet, of Barcelona, studied under Hasdai Crescas and Rabbi Nissim ben Reuben Gerondi. Nissim ben Reuben Gerondi, was a steadfast Rationalist who did not hesitate to refute leading authorities, such as Rashi, Rabbeinu Tam, Moses ben Nahman, and Solomon ben Adret. The pogroms of 1391, against Jews of Spain, forced Isaac to flee to Algiers - where he lived out his life. Isaac's responsa evidence a profound knowledge of the philosophical writings of his time; in one of Responsa No. 118 he explains the difference between the opinion of Gersonides and that of Abraham ben David of Posquières on free will, and gives his own views on the subject. He was an adversary of Kabbalah who never spoke of the Sefirot; he quotes another philosopher when reproaching kabbalists with "believing in the "Ten" (Sefirot) as the Christians believe in the Trinity" [19].

Hasdai ben Judah Crescas

Hasdai Crescas, of Barcelona, was a leading rationalist on issues of natural law and free-will. His views can be seen as precursors to Baruch Spinoza. His work, Or Adonai, became a classic refutation of medieval Aristotelism, and harbinger of the scientific revolution in the 16th century. Hasdai Crescas was a student of Nissim ben Reuben Gerondi, who in turn was a student of Reuben ben Nissim Gerondi. Crescas was not a Rabbi, yet he was active as a teacher. Among his fellow students and friends, his best friend was Isaac ben Sheshet Perfet. Cresca's students won accolades as participants in the Disputation of Tortosa.

Joseph Albo

Joseph Albo, of Monreal, was a student of Hasdai Crescas. He wrote Sefer ha-Ikkarim ("Book of Principles"), a classic work on the fundamentals of Judaism. Albo narrows the fundamental Jewish principles of faith from thirteen to three -

-

-

-

-

-

-

- belief in the existence of Hashem,

- belief in revelation, and

- belief in divine justice, as related to the idea of immortality.

-

-

-

-

-

Albo rejects the assumption that creation ex nihilo is essential in belief in Hashem. Albo freely criticizes Maimonides' thirteen principles of belief and Crescas' six principles. According to Albo, "belief in the Messiah is only a 'twig' unnecessary to the soundness of the trunk"; not essentnial to Judaism. Nor is it true, according to Albo, that every law is binding. Though every ordinance has the power of conferring happiness in its observance, it is not true that every law must be observed, or that through the neglect of a part of the law, a Jew would violate the divine covenant or be damned. Contemporary Orthodox Jews, however, vehemently disagree with Albo's position believing that all Jews are divinely obligated to fulfill every applicable commandment.

Hoter ben Solomon

Hoter ben Shlomo was a scholar and philosopher in Yemen heavily influenced by Nethanel ben al-Fayyumi, Maimonides, Saadia Gaon and al-Ghazali. The connection between the "Epistle of the Brethren of Purity" and Ismailism suggests the adoption of this work as one of the main sources of what would become known as "Jewish Ismailism” as found in Late Medieval Yemenite Judaism. “Jewish Ismailism” consisted of adapting, to Judaism, a few Ismaili doctrines about cosmology, prophecy, and hermeneutics. There are many examples of the Brethren of Purity influencing Yemenite Jewish philosophers and authors in the period 1150–1550.[20] Some traces of Brethren of Purity doctrines, as well as of their numerology, are found in two Yemenite philosophical midrashim written in 1420–1430: Midrash ha-hefez ("The Glad Learning") by Zerahyah ha-Rofé (a/k/a Yahya al-Tabib) and the Siraj al-‘uqul ("Lamp of Intellects") by Hoter ben Solomon.

Don Isaac Abravanel

Isaac Abravanel, statesman, philosopher, Bible commentator, and financier who commented on Maimonides' thirteen principles in his Rosh Amanah. Isaac Abravanel was steeped in Rationalism by the Ibn Yahya family, who had a residence immediately adjacent to the Great Synagogue of Lisbon (also built by the Ibn Yahya Family). His most important work, Rosh Amanah ("The Pinnacle of Faith"), defends Maimonides' thirteen articles of belief against attacks of Hasdai Crescas and Yosef Albo. Rosh Amanah ends with the statement that "Maimonides compiled these articles merely in accordance with the fashion of other nations, which set up axioms or fundamental principles for their science".

Isaac Abravanel was born and raised in Lisbon; a student of the Rabbi of Lisbon, Yosef ben Shlomo Ibn Yahya[21]. Rabbi Yosef was a poet, religious scholar, rebuilder of Ibn Yahya Synagogue of Calatayud, well versed in rabbinic literature and in the learning of his time, devoting his early years to the study of Jewish philosophy. The Ibn Yahya family were renowned physicians, philosophers and accomplished aides to the Portuguese Monarchy for centuries.

Isaac's grand-father, Samuel Abravanel, was forcibly converted to Christianity during the pogroms of 1391 and took the Spanish name "Juan Sanchez de Sevilla". Samuel fled Castile-Leon, Spain, in 1397 for Lisbon, Portugal, and reverted to Judaism - shedding his Converso after living among Christians for six years. Conversions outside Judaism, coersed or otherwise, had a strong impact upon young Isaac later compelling him to forfeit his immense wealth in an attempt to redeem Iberian Jewry from coercion of the Alhambra Decree. There are parallels between what he writes, and documents produced by Inquisitors, that present conversos as ambivalent to Christianity and sometimes even ironic in their expressions regarding their new religion - crypto-jews.

Leone Ebreo

Judah Leon Abravanel was Portuguese physician, poet and philosopher. His work Dialoghi d'amore ("Dialogues of Love"), written in Italian, was one of the most important philosophical works of his time In an attempt to circumvent a plot, hatched by local Catholic Bishops to kidnap his son, Judah sent his son from Castile, to Portugal with a nurse, but by order of the king, the son was seized and baptized. This was a devastating insult to Judah and his family, and was a source of bitterness throughout Judah’s life and the topic of his writings years later; especially since this was not the first time the Abravanel Family was subjected to such embarrassment at the hands of the Catholic Church.

Judah's Dialoghi is regarded as the finest of Humanistic Period works. His neoplatonism is derived from the Hispanic Jewish community, especially the works of Ibn Gabirol. Platonic notions of reaching towards a nearly impossible ideal of beauty, wisdom, and perfection encompass the whole of his work. In Dialoghi d'amore, Judah defines love in philosophical terms. He structures his three dialogues as a conversation between two abstract “characters”: Philo, representing love or appetite, and Sophia, representing science or wisdom, Philo+Sophia (philosophia).

Notable Jewish philosophers post-Maimonides

- Hillel of Verona

- Jedaiah ben Abraham Bedersi

- Simeon ben Zemah Duran

- Nissim of Gerona

- Jacob ben Machir ibn Tibbon

- Joseph Caspi a/k/a Joseph ben Abba Mari ibn Kaspi

- Isaac Nathan ben Kalonymus

- Judah Messer Leon

- David ben Judah Messer Leon

- Obadiah ben Jacob Sforno

- Judah Moscato

- Azariah dei Rossi

- Isaac Aboab I

- Isaac Campanton a/k/a "the gaon of Castile."

- Isaac ben Moses Arama

- Profiat Duran a Converso, Duran wrote Be Not Like Your Fathers

Renaissance Jewish philosophy and philosophers

Some of the Monarchies of Asia Minor and European welcomed expelled Jewish Merchants, scholars and theologians. Divergent Jewish philosophies evolved against the backdrop of new cultures, new languages and renewed theological exchange. Philosophic exploration continued through the Renaissance period as the center-of-mass of Jewish Scholarship shifted to France, Germany, Italy, and Turkey.

Elias ben Moise del Medigo

Elia del Medigo was a descendant of Judah ben Eliezer ha-Levi Minz and Moses ben Isaac ha-Levi Minz. Eli'ezer del Medigo, of Rome, received the surname "Del Medigo" after studying Medicine. The name was later changed from Del Medigo to Ha-rofeh. He was the father and teacher of a long line of rationalist philosophers and scholars. Non-Jewish students of Delmedigo classified him as an “Averroist”, however, he saw himself as a follower of Maimonides. Scholastic association of Maimonides and Ibn Rushd would have been a natural one; Maimonides, towards the end of his life, was impressed with the Ibn Rushd commentaries and recommended them to his students. The followers of Maimonides (Maimonideans) had therefore been, for several generations before Delmedigo, the leading users, translators and disseminators of the works of Ibn Rushd in Jewish circles, and advocates for Ibn Rushd even after Islamic rejection of his radical views. Maimonideans regarded Maimonides and Ibn Rushd as following the same general line. In his book, Delmedigo portrays himself as defender of Maimonidean Judaism, and — like many Maimonideans — he emphasized the rationality of Jewish tradition.

Moses Almosnino

Moses Almosnino was born Thessaloniki 1515 - died Constantinople abt 1580. He was a student of Levi Ibn Habib, who was in turn a student of Jacob ibn Habib, who was, in turn, a student of Nissim ben Reuben.

Moses ben Jehiel Ha-Kohen Porto-Rafa (Rapaport)

Moses ben Jehiel Ha-Kohen Porto-Rafa (Rapaport), was a member of the German family "Rafa" (from whom the Delmedigo family originates) that settled in the town of Porto in the vicinity of Verona, Italy, and became the progenitors of the renowned Rapaport Rabbinic family. In 1602 Moses served as rabbi of Badia Polesine in Piedmont. Moses was a friend of Leon Modena[22].

Abraham ben Judah ha-Levi Minz

Abraham ben Judah ha-Levi Minz was an Italian rabbi who flourished at Padua in the first half of the 16th century, father-in-law of Meïr Katzenellenbogen. Minz studied chiefly under his father, Judah Minz, whom he succeeded as rabbi and head of the yeshiva of Padua.

Meir ben Isaac Katzellenbogen

Meir ben Isaac Katzellenbogen was born in Prague where together with Shalom Shachna he studied under Jacob Pollak. Many rabbis, including Moses Isserles, addressed him in their responsa as the "av bet din of the republic of Venice." The great scholars of the Renaissance with whom he corresponded include Shmuel ben Moshe di Modena, Joseph Katz, Solomon Luria, Moses Isserles, Obadiah Sforno, and Moses Alashkar.

Elijah Ba'al Shem of Chelm

Rabbi Elijah Ba'al Shem of Chelm was a student of Rabbi Solomon Luria who was, in turn a student of Rabbi Shalom Shachna - father-in-law and teacher of Moses Isserles. Elijah Ba'al Shem of Chelm was also a cousin of Moses Isserles.

Eliezer ben Elijah Ashkenazi

Rabbi Eliezer ben Elijah Ashkenazi Ha-rofeh Ashkenazi of Nicosia ("the physician") the author of Yosif Lekah on the Book of Esther.

Notable Renaissance Jewish philosophers

- Francisco Sanches

- Miguel de Barrios

- Uriel da Costa

Jewish philosophers of the Enlightenment

With expulsion from Spain came the dissemination of Jewish Philosophical investigation throughout the Mediterranean Basin, Northern Europe and Western Hemisphere. The center-of-mass of Rationalism shifts to France, Italy, Germany, Crete, Sicily and Netherlands. Expulsion from Spain and the coordinated pogroms of Europe resulted in the cross-pollenation of variations on Rationalism incubated within diverse communities. This period is also marked by the intellectual exchange among leaders of the Christian Reformation and Jewish scholars. Of particular note is the line of Rationalists who migrate out of Germany, and present-day Italy into Crete, and other areas of the Ottoman Empire seeking safety and protection from the endless pogroms fomented by the House of Habsburg and the Roman Catholic Church against Jews.

Rationalism was incubating in geographies far from Spain. From stories told by Rabbi Elijah Ba'al Shem of Chelm, German-speaking Jews, descendants of Jews who migrated back to Jerusalem after Charlemagne's invitation was revoked in Germany many centuries earlier, who lived in Jerusalem during the 11th century were influenced by prevailing Mutazilite scholars of Jerusalem. A German-speaking Palestinian Jew saved the life of a young German man surnamed "Dolberger". When the knights of the First Crusade came to siege Jerusalem, one of Dolberger's family members rescued German-speaking Jews in Palestine and brought them back to the safety of Worms, Germany, to repay the favor.[23] Further evidence of German communities in the holy city comes in the form of halakic questions sent from Germany to Jerusalem during the second half of the eleventh century[24].

All of the foregoing resulted in an explosion of new ideas and philosophic paths. There were, however, notable contributors who catalyzed philosophic thought of normative Rabbinic Judaism of today. Those most notable contributors to contemporary Jewish Philosophy are noted below -

Yosef Shlomo ben Eliyahu Dal Medigo

Joseph Solomon Delmedigo was a physician and teacher - Baruch Spinoza was a student of his works[25].

Baruch Spinoza

Baruch Spinoza adopted Pantheism, broke with Rabbinic Judaism tradition and was excommunicated. Nevertheless the Jewish influence in his work from Maimonides and Leone Ebreo, is evident. Some contemporary critics (e.g. Wachter, Der Spinozismus im Judenthum) claimed to detect the influence of the Kabbalah, while others (e.g. Leibniz) regarded Spinozism as a revival of Averroism; a talmudist manner of referencing to Maimonidean Rationalism.

Tzvi Hirsch ben Yaakov Ashkenazi

Rabbi Tzvi Hirsch ben Yaakov Ashkenazi was a student of his father, but most notably also a student of his grandfather Rabbi Elijah Ba'al Shem of Chelm.

Jacob Emden

Rabbi Jacob Emden was a student of his father Rabbi Tzvi Hirsch ben Yaakov Ashkenazi a Rabbi in Amsterdam. Emden, a steadfast Talmudist, was a prominent opponent of the Sabbateans (Messianic Kabbalists who followed Sabbatai Tzvi). Though anti-Maimonidean, Emden should be noted for his critical examination of the Zohar concluding that large parts of it were forged.

Kabbalah

The word "Kabbalah" was used in medieval Jewish texts to mean "tradition", see Abraham Ibn Daud's Sefer Ha-Qabbalah also known as the "Book of our Tradition". "Book of our Tradition" does not refer to mysticism of any kind - it chronicles "our tradition of scholarship and study" in two Babylonian Academies, through the Geonim, into Talmudic Yeshivas of Spain. In Talmudic times there was a mystic tradition in Judaism, known as Maaseh Bereshith (the work of creation) and Maaseh Merkavah (the work of the chariot); Maimonides interprets these texts as referring to Aristotelian physics and metaphysics as interpreted in the light of Torah.

Criticism of mysticism and esoteric methods

-

- Saadia Gaon teaches in his book Emunot v'Deot that Jews who believe in gilgul have adopted a non-Jewish belief.

-

- Maimonides rejected many texts of Heichalot, particularly Shi'ur Qomah whose anthropomorphic vision of HaShem he considered heretical.

-

- Meir ben Simon of Narbonne wrote an epistle (included in Milhhemet Mitzvah) against early Kabbalists, singled out Sefer Bahir, rejecting the attribution of its authorship to the tanna R. Nehhunya ben ha-Kanah and describing some of its content as follow -

-

- "... And we have heard that a book had already been written for them, which they call Bahir, that is 'bright' but no light shines through it. This book has come into our hands and we have found that they falsely attribute it to Rabbi Nehunya ben Haqqanah. God forbid! There is no truth in this... The language of the book and its whole content show that it is the work of someone who lacked command of either literary language or good style, and in many passages it contains words which are out and out heresy."

-

- Rabbi Leone di Modena wrote that if we were to accept the Kabbalah, then the Christian trinity would indeed be compatible with Judaism, as the Trinity closely resembles the Kabbalistic doctrine of the Sefirot.

-

- Rabbi Yihhyah Qafahh wrote a book entitled Milhhamoth HaShem, (Wars of the L-RD) against what he perceived as the false teachings of the Zohar and the false Kabbalah of Isaac Luria. He is credited with spearheading the Dor Daim.

-

- Rabbi Yeshayahu Leibowitz publicly shared the views expressed in Rabbi Yihhyah Qafahh's book Milhhamoth HaShem and elaborated upon these views in his many writings.

Post-Emancipation Jewish philosophers and philosophies

- Samuel Hirsch (belonging to Reform Judaism.)

- Samson Raphael Hirsch philosophy of Torah im Derech Eretz; belonged to the Neo-Orthodox movement of 19th century Germany, combating Reform Judaism

- Jacob Abendana Sephardic Rabbi and Philosopher

- Isaac Cardoso

- David Nieto Sephardic Rabbi and Philosopher

- Isaac Orobio de Castro Sephardic Rabbi and Philosopher

- Moses Mendelssohn German Jewish philosopher Jerusalem oder über religiöse Macht und Judentum (1783)

- Samuel David Luzzatto Sephardic Rabbi and Philosopher

- Elijah Benamozegh Sephardic Rabbi and Philosopher

- Moses Hess a secular Jewish philosopher and one of the founders of socialism.

- Jehuda Leib Schwarzmann was a Russian-Jewish existentialist philosopher.

- Hermann Cohen

Contemporary Jewish philosophers

Sephardic philosophers and scholars

- Thomas Nagel a Serbia-born Jewish Philosopher, though not necessarily embraced by prevailing talmudic authorities.

- Paul R. Mendes-Flohr

- Rabbi Dr. Jose Faur Argentine-born

Ashkenazi Philosophers and scholars

- Eliezer Berkovits

- Eliyahu Eliezer Dessler

- Daniel Rynhold

- Samson Raphael Hirsch

- Monsieur Chouchani

- Emmanuel Levinas a French philosopher and Talmudic commentator

- Joseph Soloveitchik - "The Rav"

- David Hartman (rabbi)

- Yeshayahu Leibowitz

Philosophers and scholars of Conservative Judaism

- Bradley Shavit Artson

- Elliot N. Dorff

- Neil Gillman

- Abraham Joshua Heschel

- Max Kadushin

- William E. Kaufman

Philosophers of Reform Judaism

- Emil Fackenheim

- Eugene Borowitz

Philosophers of Progressive movement in Judaism

- Leo Baeck

Contemporary Jewish philosophies

Jewish existentialism

One of the major trends in contemporary Jewish philosophy was the attempt to develop a theory of Judaism through existentialism. One of the primary players in this field was Franz Rosenzweig. While researching his doctoral dissertation on the 19th-century German philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Rosenzweig reacted against Hegel's idealism and favored an existential approach. Rosenzweig, for a time, considered conversion to Christianity, but in 1913, he turned to Jewish philosophy. He became a philosopher and student of Hermann Cohen. Rozensweig's major work, Star of Redemption, is his new philosophy in which he portrays the relationships between HaShem, humanity and world as they are connected by creation, revelation and redemption. Later Jewish existentialists include Conservative rabbis Neil Gillman and Elliot N. Dorff.

Revival of rationalism

Re-invigoration of Rationalism is a rapidly growing movement among religious and secular Jews. Dor Daim, and Rambamists are two groups who reject mysticism as a "superstitious innovation" to an otherwise clear and succinct set of Laws and rules. Reviving Rationalism can be seen as "Restorationist"; reaching back in time for tools to simplify Rabbinic Judaism and bring all Jews, regardless of status or stream of Judaism, closer to observance of Halacha, Mitzvot and Kashrut.

According to Rationalists, there is shame and disgrace attached to failure to investigate matters of religious principle using the fullest powers of human reason and intellect. One cannot be considered wise, or perceptive, if one does not attempt to understand the origins, and establish the correctness, of one's beliefs.

The suggestion of a "religion of reason" has caused many scholars and skeptics to dismiss, as foolhardy, any effort to reconcile religion and reason using our intellect. Some scholars argue that inevitable "tortured reconciliations" forfeit the original meaning and message of the text, while those inclined to skepticism will wonder at the usefulness of a document whose only apparent remaining purpose is to be periodically "reconciled" with external evidence.

Reconstructionist theology

Perhaps the most controversial form of Jewish philosophy that developed in the early 20th century was the religious naturalism of Rabbi Mordecai Kaplan. His theology was a variant of John Dewey's philosophy. Dewey's naturalism combined atheist beliefs with religious terminology in order to construct a philosophy for those who had lost faith in traditional Judaism. In agreement with the classical medieval Jewish thinkers, Kaplan affirmed that HaShem is not personal, and that all anthropomorphic descriptions of HaShem are, at best, imperfect metaphors. Kaplan's theology went beyond this to claim that HaShem is the sum of all natural processes that allow man to become self-fulfilled. Kaplan wrote that "to believe in HaShem means to take for granted that it is man's destiny to rise above the brute and to eliminate all forms of violence and exploitation from human society."

Haredi theology

Contemporary Haredim consider the fusion of religion and philosophy as difficult because classical philosophers start with no preconditions for which conclusions they must reach in their investigation, while classical religious believers have a set of religious principles of faith that they hold one must believe.

Some Haredim contend that one cannot simultaneously be a philosopher and a true adherent of a revealed religion. In this view, all attempts at synthesis ultimately fail. For example, Rabbi Nachman of Breslov, views all philosophy as untrue and heretical. In this he represents one strand of Hasidic thought, with creative emphasis on the emotions. Conversely, Baruch Spinoza, a pantheist, views revealed religion as inferior to philosophy, and thus saw traditional Jewish Religious dogma as an intellectual failure.

In the texts of Chabad, Hasidut is seen as able to unite all parts of Torah thought, from the schools of philosophy to mysticism, by uncovering the illuminating Divine essence that permeates and transcends all approaches. One example of this is given by Schneur Zalman of Liadi in the early chapters of the Tanya. In a parenthetical side-column to the main text, Kabbalists are said to agree with Maimonides' description that "HaShem is the knower, the knowledge, and the known", but that this statement only applies to certain, stated Kabbalistic levels of Divinity, and no higher.

Hasidic Theosophy

Hasidic Theosophy is the thought and teachings of the Hasidic movement founded by the Baal Shem Tov. It expresses esoteric Lurianic Kabbalistic methods in a new paradigm in relation to man, and so could be conveyed to the Jewish masses. As the movement grew, it developed into various different interpretations, formed by the circles of close followers of the Baal Shem Tov, and his successor Dov Ber of Mezeritch. In the school of Chabad, formed by Schneur Zalman of Liadi, the mystical revivalism of the early Hasidic Masters was brought into a systematic philosophical articulation, that brought the esoteric Kabbalah of Isaac Luria into understanding. Interpreting the verse from Job, "from my flesh I see HaShem", Shneur Zalman explained the inner meaning, or "soul", of the Jewish mystical tradition in intellectual form, by means of analogies drawn from the human realm. As explained and continued by the later leaders of Chabad, this enabled the human mind to grasp concepts of Godliness, and so enable the heart to feel the love and awe of HaShem, emphasised by all the founders of hasidism, in an internal way. This development, the culminating level of the Jewish mystical tradition, in this way bridges philosophy and mysticism, by expressing the transcendent in human terms.

Non-Orthodox revival of Kabbalah

Jewish religious thinking in the latter 20th century saw resurgent interest in Kabbalah. In academic studies, Gershom Scholem began the critical investigation of Jewish mysticism, while in non-Orthodox Jewish denominations, Jewish Renewal and Neo-Hasidism, spiritualised worship. Many philosophers do not consider this a form of philosophy, as Kabbalah is a collection of esotric methods of textual interpretation. Mysticism is generally understood as an alternative to philosophy, not a variant of philosophy.

Process theology

A recent trend has been to reframe Jewish theology through the lens of process philosophy, more specifically process theology. Process philosophy suggests that fundamental elements of the universe are occasions of experience. According to this notion, what people commonly think of as concrete objects are actually successions of these occasions of experience. Occasions of experience can be collected into groupings; something complex such as a human being is thus a grouping of many smaller occasions of experience. In this view, everything in the universe is characterized by experience (not to be confused with consciousness); there is no mind-body duality under this system, because "mind" is simply seen as a very developed kind of experiencing entity.

Intrinsic to this worldview is the notion that all experiences are influenced by prior experiences, and will influence all future experiences. This process of influencing is never deterministic; an occasion of experience consists of a process of comprehending other experiences, and then reacting to it. This is the "process" in "process philosophy". Process philosophy gives HaShem a special place in the universe of occasions of experience. HaShem encompasses all the other occasions of experience but also transcends them; thus process philosophy is a form of panentheism.

The original ideas of process theology were developed by Charles Hartshorne (1897–2000), and influenced a number of Jewish theologians, including British philosopher Samuel Alexander (1859–1938), and Rabbis Max Kaddushin, Milton Steinberg and Levi A. Olan, Harry Slominsky and to a lesser degree, Abraham Joshua Heschel.

Holocaust theology

Judaism has traditionally taught that HaShem is omnipotent, omniscient and omnibenevolent. Yet, these claims are in jarring contrast with the fact that there is much evil in the world. Perhaps the most difficult question that monotheists have confronted is "how can one reconcile the existence of this view of HaShem with the existence of evil?" or "how can there be good without bad?" "how can there be a God without a devil?" This is the problem of evil. Within all monotheistic faiths many answers (theodicies) have been proposed. However, in light of the magnitude of evil seen in the Holocaust, many people have re-examined classical views on this subject. How can people still have any kind of faith after the Holocaust? This set of Jewish philosophies is discussed in the article on Holocaust theology.

See also

- Jewish history

- Jewish principles of faith

- Kabbalah

- Jewish existentialism

- Jewish denominations

References

- Daniel H. Frank and Oliver Leaman (eds.), History of Jewish Philosophy. London: Routledge, 1997. ISBN 0-415-08064-9

- Colette Sirat, A History of Jewish Philosophy in the Middle Ages. Cambridge University Press, 1990. ISBN 0-521-39727-8

- ↑ "The Melchizedek Tradition: A Critical Examination of the Sources to the Fifth Century ad and in the Epistle to the Hebrews", by Fred L. Horton, Jr., Pg. 54, Cambridge University Press, 2005, ISBN 0-521-01871-4

- ↑ "Sefer Yetzirah", By Aryeh Kaplan, xii, Red Wheel, 1997, ISBN 0-87728-855-0

- ↑ Bereishit Rabba (39,1)

- ↑ http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/view.jsp?artid=281&letter=P

- ↑ "Christianity, Judaism and other Greco-Roman cults: studies for Morton Smith at sixty", Volume 12,Part 1, Pg 110, Volume 12 of Studies in Judaism in late antiquity, by Jacob Neusner ann Morton Smith, Brill 1975, ISBN 90-04-04215-6

- ↑ "Beginnings in Jewish Philosophy", By Meyer Levin, Pg 49, Behrman House 1971, ISBN 0-87441-063-0

- ↑ "Geonica", By Ginzberg Louis, Pg. 18, ISBN 1-110-35511-4

- ↑ s.v. al-Djubba'i, The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Vol. 2: C–G. 2 (New ed.). Leiden: E. J. Brill. 1965. ISBN 90 04 07026 5.

- ↑ W. Montgomery Watt, Free will and predestination in early Islam, London 1948, 83-7, 136-7.

- ↑ A'asam, Abdul-Amîr al-Ibn al-Rawandi's Kitab Fahijat al-Mu'tazila: Analytical Study of Ibn al-Riwandi's Method in his Criticism of the Rational Foundation of Polemics in Islam. Beirut-Paris: Editions Oueidat, 1975–1977

- ↑ A history of Jewish philosophy in the Middle Ages By Colette Sirat

- ↑ http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/view.jsp?artid=134&letter=B&search=Bahya#ixzz0Tx3CqjNq

- ↑ Or Adonai, ch. i.

- ↑ Stroumsa, S. (1993) 'On the Maimonidean Controversy in the East: the Role of Abu 'l-Barakat al-Baghdadi', in H. Ben-Shammai (ed.) Hebrew and Arabic Studies in Honour of Joshua Blau, Tel Aviv and Jerusalem. (On the role of Abu 'l-Barakat's writings in the resurrection controversy of the twelfth century; in Hebrew.)

- ↑ The encyclopædia britannica: a dictionary of arts, sciences ..., Volume 13 edited by Hugh Chisholm, Pg 174

- ↑ A short biographical article about Rabeinu Shem Tov Ben Yosef Falaquera, one of the great Rishonim who was a defender of the Rambam, and the author of the Moreh HaMoreh on the Rambam's Moreh Nevuchim. Published in the Jewish Quarterly Review journal (Vol .1 1910/1911).

- ↑ Torah and Sophia: The Life and Thought of Shem Tov Ibn Falaquera (Monographs of the Hebrew Union College) by Raphael Jospe

- ↑ ^ Jacobs, Louis (1990). Hashem, Torah, Israel: traditionalism without fundamentalism. Cincinnati: Hebrew Union College Press. ISBN 0-87820-052-5. OCLC 21039224

- ↑ Responsa No. 159

- ↑ D. Blumenthal, "An Illustration of the Concept 'Philosophic Mysticism' from Fifteenth Century Yemen," and "A Philosophical-Mystical Interpretation of a Shi'ur Qomah Text."

- ↑ "Isaac Abarbanel's stance toward tradition: defense, dissent, and dialogue" By Eric Lawee

- ↑ http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/judaica/ejud_0002_0016_0_16007.html

- ↑ Seder ha-Dorot", p. 252, 1878 ed]

- ↑ Epstein, in "Monatsschrift", xlvii. 344; Jerusalem: Under the Arabs

- ↑ "Blesséd Spinoza: a biography of the philosopher", by Lewis Browne, The Macmillan Company, 1932, University of Wisconsin - Madison

External links

- Adventures in Philosophy - Jewish Philosophy Index (radicalacademy.com)

- Survey of Jewish Philosophy (jct.ac.il)

- Jewish Philosophy, The Dictionary of Philosophy (Dagobert D. Runes)

- Rabbi Haim Lifshitz-articles review Jewish Philosophy

- Rabbi Marc Angel's Project reflecting a fusion of Modern Orthodoxy and Sephardic Judaism

- "Machone Torath Moshe" with many contributions by Rabbi Michael Shelomo Bar-Ron

Further reading

- (Hebrew) Material by topic, daat.ac.il

- (Hebrew) and (English) Primary Sources, Ben Gurion University

- (English) Online materials, Halacha Brura Institute

- (Hebrew) From the Israeli high-school syllabus, education.gov.il

- (English) Articles on Jewish Philosophy-Haim Lifshitz and Isaac Lifshitz

- (English) Free will in Jewish Philosophy

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||